Would you get to enjoy the same serenity, the same beautiful beach or shoreline in the future, let’s say after 50 years from now? Would it increase its extent for you to enjoy, or would it dwindle due to erosion? How do river estuaries vanish? Let’s visit ‘Marina Beach’ – the world’s second longest beach in Chennai, to get answers to our questions.

A 14 kilometers long continuous stretch of sand, Marina Beach extends from the Cooum estuary (near Fort St. George) in the north to the Adyar estuary (around Besant Nagar) in the south. An estuary draining into the Ocean is part of a large river up to which the tidal waters flushing take place. The world famous natural beach developed gradually by the trapping and deposition of sediments, over the course of a century, primarily attributed to the construction of man-made/artificial Chennai Port.

Waves and tides are the architects of a shoreline. Currents induced through them propagate along the coast and transfer sediments from one point to another. Is the shoreline along the Chennai city stable? If unstable, is it accreting sediment or is it losing its existence to erosion? What places along the shoreline are being affected? A study carried out by Prof.Vallam Sundar, Prof. S.A. Sannasiraj and Ms. R. G. M. Mary at the Department of Ocean Engineering, IIT Madras, just answers the concerns.

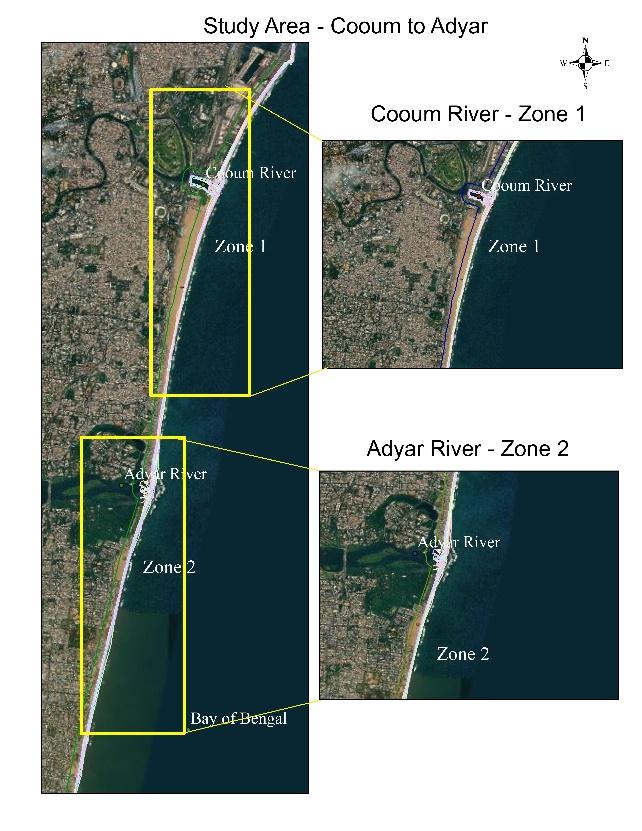

Using the satellite-imagery data for a period of 20 years, 2000-2019, they calculated the changes in Marina beach shoreline and found that the accretion of sediments occurred about 5.6km along the urban part of the Marina beach and the Cooum region (Zone 1). Whereas the 9 km region extending northward from Adyar river mouth (Zone 2) exhibited an eroding trend. The annual net transportation of sediments is northern along the coast. The satellite imagery of the study area is given in Figure 1.

Credits: Google Earth

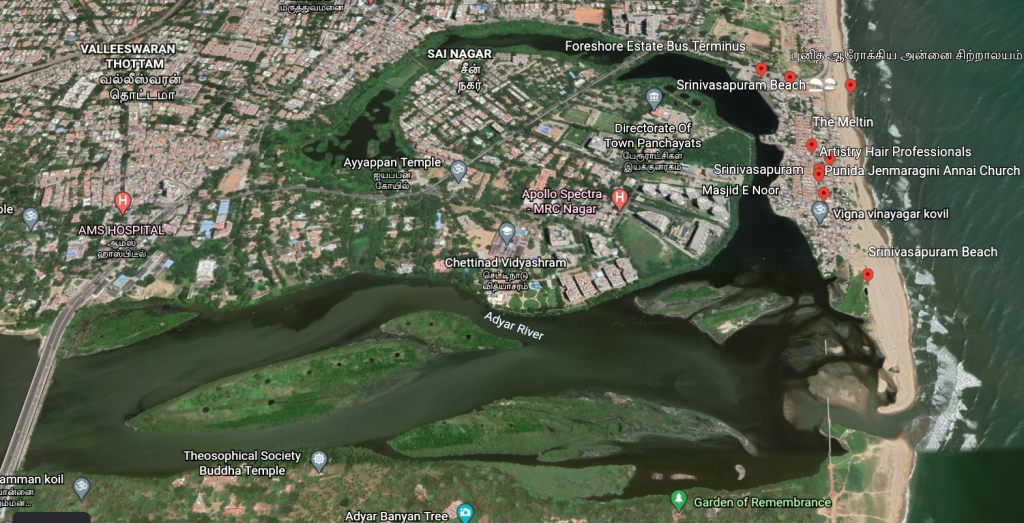

“The maximum erosion being reported at Srinivasapuram, a densely populated coastal hamlet immediately north of river Adyar’s mouth” highlighted Dr. L. Sheela Nair, Scientist F at the National Center for Earth Science Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, who was not involved in this study. “This particular site experienced about 50 meters of erosion in 2005, subsequent to the 2004 Tsunami. Since then, the erosion trend has been continuing” she added.

But, how would that affect the inhabitants of Srinivasapuram? “A large population of this hamlet relies on fishing for their livelihood. So, immediate attention is needed to protect them by adopting appropriate coastal protection measures following a scientific approach” she explained. The circumstances are deeper than they sound!

Sediments being transported by wave-currents along the shoreline get easily deposited in the sinkholes – regions of increased water depths. Mouths of the Adyar and Cooum rivers are the major sinkholes for trapping these sediments, which results in the shallowing of the rivers’ mouths. Now, the northern shore of the Adyar river’s mouth (where Srinivaspuram lies) experiences progressive erosion, the sediment drift there is dominant towards the south. This results in the formation of spits and sandbars, reducing the width of the Adyar’s inlet (Figure 2).

“This might completely block the Adyar river’s mouth within a few years, thus, preventing exchange of water between the river and the sea”, cautioned Prof. Sundar, the consequences of which are well known.

In the case of Cooum river mouth (Figure 3), repeated efforts have been carried by the Tamil Nadu Public Works Department in dredging its bed. However, minimum, or no tidal flushing occurs in the absence of monsoon, resulting in the stagnation of water in the Cooum mouth. What prevention measures can help us in saving the Adyar & Cooum estuaries?

“Construction of a pair of training walls would help us prevent sandbar and spit formations in both the river mouths” answered Prof. Sundar. “Transitional Groins would be helpful in protecting the downward eroding shoreline at Srinivasapuram, in addition to trapping of sediments” he added. Training walls are constructed to constrain the flow of a river at its estuary. Groins are structures constructed perpendicular to the shore to control the movement of sediments by longshore sediment transport.

“Another side of the coin is to see our coast as an eye sore with a series of groins along the city’s major tourist attraction” remarked Prof. Sundar, on saving the Chennai shoreline. “The lost beach could never be retrieved with seawalls. For the present affected stretch of the eastern coast, a combination of training walls for training the river mouths and transitional groins fields can be the best possible solution, as they are easier and faster to construct and maintain, compared to other approaches. Groins have been proved to be sustainable as well” he elaborated.

“The groin field along the Royapuram stretch and the west coast of Tamilnadu are standing examples having sustained over one and half decades” he asserted further.

“In a longer run, we could avoid construction of longer seawall sections which prevent the aesthetic view of sea, like on the coastal roads in Pondicherry and Mumbai”.

Article by Mywish Anand

Here is the original link to the scientific paper:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1064119X.2020.1856241